Beauty, Terror and the Sublime

The Sublime is not strictly speaking something which is proven or demonstrated, but a marvel, which seizes one, strikes one, and makes one feel.

Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux

The passion caused by the great and Sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully is astonishment, and astonishment is that state of the soul in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror.

Edmund Burke

Recently I have been teasing out my understanding of and feelings around the concept of the Sublime. I get quite tangled up in picking apart how the idea of beauty fits into the contemporary art world and where the sublime can take its place or, perhaps, exist along side it.

I find the concept of beauty very difficult to conceptualise. In a traditional art sense it is tied up in ideals around formal harmony and elegance, but this is only one aspect of the way we experience beauty. Beauty is far more than just visual pleasure and prettiness - these things can be expressed by the decorative and without having a visceral impact on the viewer. The aspects of beauty that interest me are far closer to those expressed by the sublime.

In everyday parlance the word 'sublime' might still evoke something that is elevated or lofty, but it is in the soft guise of being pleasing, delectable and existing in positive way. For example; 'this strawberry ice cream is sublime'. We don't tend to use it in its truer sense; to describe something that induces awe or a sense of the overwhelm, for which it is used in an art or philosophy context.

The word comes from the latin sublimus where 'limen' is a threshold, boundary or limit. It also has a cousin in the alchemical concept of sublimare - to elevate, purify and transform. So for something to be sublime it must be pushing right up to the limits. I would say that in this respect it can be used in tandem with the concept of beauty, where beauty is right at the limits of enjoyment, where the experience of the beauty becomes overwhelming. This is not the beauty of something pretty or conforming to standards, this is a beauty that bursts past reason and strikes the viewer like a fist to the heart.

Philosophers have attempted to quantify the nature of the sublime and, as with most terms used in an art context, the meanings has shifted subtly over time. There are many ideas about what this means: impressive, awe-inspiring, lofty, exalted, something terrifying that inspires a strange pleasure in the terror. The first century Greek author known as (Pseudo) Longinus described 'The True Sublime" in Book 7 of the Peri Hypsous:

"For by some innate power the true sublime uplifts our souls; we are filled with a proud exaltation and a sense of vaunting joy; just as though we had ourselves produced what we had heard."

Riding, C. and Llewellyn, N. (2009) British Art and the Sublime

By the time of the Enlightenment the sublime was regarded as of such exalted status that it was beyond normal experience. Whether physical or metaphysical, the sublime was generally regarded as past comprehension and measurement - a thing so great, so vast and so awe inspiring that it was beyond human understanding.

In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain, the sublime was associated in particular with human responses to the immensity or turbulence of the natural world. Consequently, sublime landscape painters, especially in the Romantic period, tended to take subjects such as towering mountain ranges, deep chasms, violent storms, rough seas, volcanic eruptions or avalanches that, if actually experienced, would be dangerous and even life-threatening. In a modern context I would put forward the images of the swirling turmoil of our burning sun or the vastnesses of uncharted space. Or perhaps as the complexity of the unseeable quantum world or the immensity of the digital data being processed every second.

Edmund Burke described these awe-inspiring phenomena as being something so vast and other that it's very existences threatens the annihilation of the observer causing a contradictory experience of exaltation and terror.

On late 18th and early 19th writers Burke, Kant, Diderot, Delacroix and their contemporaries Robert Rosenblaum suggests:

"The Sublime provided a flexible semantic container for the murky new Romantic experiences of awe, terror, boundlessness and divinity that began to rupture the decorous confines of earlier aesthetic systems."

Rosenblaum, R. (1961) The Abstract Sublime

Immanuel Kant described three types of sublimity in his Critique of Judgement (1790); the awful, the lofty and the splendid. To me this really captures the varying faces of the sublime. He suggested that there is a certain pleasure in the feeling of terror experienced while knowing that you are in relative safety. You can take a strange kind of pleasure in watching a giant dust cloud roll across a desert city, marvelling at the immense power of nature, when you aren't on the ground about to be swamped by it. This causes a feeling of 'negative pleasure' which is a feeling of something deeper than pleasure, more overwhelming and all consuming.

Kant also suggests that our powers of reason allow us to at least partially mentally cope with things that are infinite or overwhelming. The power of reason over nature. The sublime experience can be any that involves deliberate subordination of oneself to some greater force.

The feeling of the Sublime is at once a feeling of displeasure arising from the inadequacy of imagination in the aesthetic estimation of magnitude to attain to its estimation of reason, and a simultaneous awakened pleasure, arresting for this very judgement of the inadequacy of sense offing in accord with ideas of reason, so far as the effort to attain to these is for us a law.

Immanuel Kant

Talking about the 'negative pleasure' response Lyotard gives an interesting insight into how beauty and the sublime can differ:

"This dislocation of the faculties among themselves gives rise to the extreme tension (Kant calls it agitation) that characterises the pathos of the sublime, as opposed to the calm feeling of beauty."

Lyotard, J.F. (1988) The Sublime and the Avant-Garde

Not to tread on the toes of a great thinker, but I'm not convinced that the feeling of beauty is always calm? I remember being struck one day by the beauty of the mountains on the central plateau to the point I was brought to tears, but considering the vast, brooding nature of the volcanoes wreathed in storm clouds I would say they fit far more into the box labelled 'sublime' than that of calm beauty. I can think of many experiences that could be labelled sublime but which I would also class as beautiful. Perhaps it's a type of beauty? Calm beauty versus overwhelming beauty?

Zizek brings some more clarity to the opposition of beauty and the sublime by quantifying their positions on opposing axes (bolding my own):

"Beauty and sublimity are opposed along the semantic axes quality-quantity, shaped-shapeless, bounded-boundless: Beauty calms and comforts; sublimity agitates and excites. 'Beauty' is the sentiment provoked when the suprasensible Idea appears in the material, sensuous medium, in its harmonious formation - a sentiment of immediate harmony between Idea and the sensuous material of its expression; white the sentiment of Sublimity is attached to chaotic, terrifying limitless phenomena."

Zizek, S. (1989) The Sublime Object of Ideology

This gives a solid definition to the meaning (and not-meaning) of beauty. In Zizek's terms beauty cannot be boundless, shapeless or of huge quantity. But is this strictly true? Is this quantifying 'beauty' or is it 'tastefulness and grace'? Whenever I try to examine the idea of beauty I think about the difference between what someone might find pretty, and what they might find beautiful in a person. Someone who is pretty or handsome is proportionate, has even skin, glossy hair, symmetrical features, usually young and without 'flaws'. While we can all agree that this person exhibits all the aspects that we, as a group, consider attractive, they might not be 'beautiful' to many of us. Beauty has another unquantifiable aspect to it which goes beyond symmetry and proportion. In fact the very aspects that can make a person physically imperfect are the same that can make them beautiful; a big crooked nose, being 'too' short or 'too' tall, having crooked teeth or wrinkles.

When explaining the unknown aspect of the sublime Lyotard discusses the same points being applied to beauty (bolding my own):

(Lyotard paraphrasing Boileau in reference to Longinus)

"The sublime, he says, cannot be taught, and didactics are thus powerless in this respect; the sublime is not linked to rules that can be determined through poetics; the sublime only requires that the reader or listener have conceptual range, taste and the ability to 'sense what everyone sense first.' Boileau therefore takes the same stand as Pére Bouhours when in 1671 the latter declared that beauty demands more than just a respect for rules, that it requires a further 'je ne sais quoi', also called genius or something 'incomprehensible and explicable', a 'gift from god', a fundamentally 'hidden] phenomenon that can be recognised only by it's effects on the addressee."

Lyotard, J.F. (1988) The Sublime and the Avant-Garde

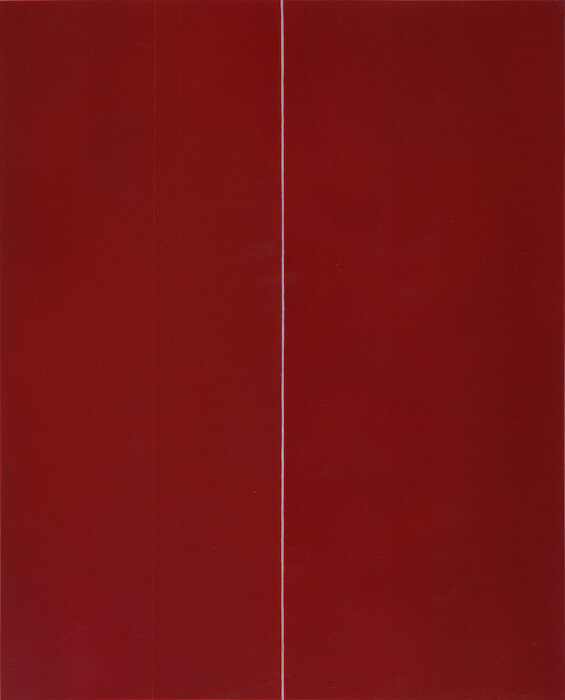

When it comes to painting vast, awe-inspiring landscapes it is easy for us to see how these artists expressed the sublime. But when the idea of the sublime made its way into the work of the abstractionists things got very curious. Without any depiction of natural forces, the very medium of the work started to carry the exalted aspects of the unknown.

"The sublime was to be abstract, devoid of all signifiers, so that which is signified will appear in all its decorum: that is, by stating it's not being there it will have the appropriate Parousia, the manifestation of the hidden essence."

LeVitte Harten, D. (1999) Creating Heaven

Parousia (Ancient Greek) means 'presence' or 'visit' which is apropos for that strange otherworldly element that makes something sublime. Without representative imagery the image is free to be the conveyer of this essence.

Lyotard suggested that the sublime is not the presentation of the unpresentable, but the presentation of the fact the unpresentable exists and I think this comes through in the abstractionist's visions of the sublime. These vast canvasses of colour and form suggest the sublime rather than presenting it to the viewer as a fait accompli.

The sublime takes place...when the imagination fails to present an object which might, if only in principle, come to match a concept.

Jean-François Lyotard

I've been thinking about the sublime in the context of the new kinds of media we can work with and I can't help thinking that both installation and video offer a way to convey the sublime that is even better than the traditional medium of painting. The sublime has such a visceral experiential quality to it that being immersed in a work could only heighten the understanding of the sublime. Watching moving image or being ensconced in an installation work brings you one step closer to the terror and awe of actually being there while still being 'safe'. What is it like to be on that storm tossed sea? To be in the very presence of a dying sun? I never got to witness Olafur Eliasson's Weather Project in the turbine hall at the Tate London, but just looking at pictures is powerful enough to help me imagine the magnitude and overwhelming presence of that huge orange sun.

Bill Viola (2005) Tristan’s ascension, video

Bill Viola's video works can have a similar effect of awe and reverence on viewers. The large-scale videos in high definition slow motion showing humans grappling with intense emotions and with the forces of nature evoke the same lofty, even spiritual emotions as a sublime painting. The difference is that video shows more than a snapshot of an image, it pulls the viewer into the moment as it unfolds.

"My world crumbles before the looming prospect of a reality that threatens to replace the foundations of the familiar. My sense of order is jumbled, my status called into question, whatever I took to be certain may be thrown into doubt. This experience of the liminal may be configured as transcendence or as transformation. The two should not be confused. Transcendence posits a mystery present in the work of art as the encounter with a metaphysical order beyond of hidden within the ordinary, sensuous world. Transformation, on the other hand, confronts enigma in the work, the disturbing sense that the world is not right."

Morgan, D. (1996) Secret Wisdom and Self-Effacement: The Spiritual in the Modern Age

I have included below some quotes I enjoy that don't fit within my writing but which I wished to include as they are interesting and speak to the sublime in postmodernism. Three are from T. McEvilley and one from artist Shirazeh Houshiary :

The mystical dimension is when knowledge is not used to construct the self as identity in terms of nationality, cultural context or gender, but to go beyond the self, where the reality of daily life is forgotten or rendered dormant. Those identities become a barrier blocking our access to the inner self; which is the place of the imagination. Daily life reality is a place of closedness, whilst imagination is one of openness. Here being is a continuous becoming. In other words, it is the moment of extreme consciousness."

Shirazeh Houshiary (1994)

"...In many ways the so-called postmodern sublime is really an oxymoron or contradiction in terms. The sublime was a basic concept of the modernist era. ... Postmodernism really does not deal in such concepts as the grandeur that bursts through the surface in a gust of frenzy. It is no worshipper of the end of the world. It does not fall on its knees before the final conflagration. It does not see the 'negative pleasure' of violence as a consummation. Really, taking the sublime in the old sense, there is no postmodern sublime."

McEvilley, T. (2001) Turned Upside Down and Torn Apart

"If the sublime, in its weakened postmodern forms, is still seen to as dangerous, then the meaning of its danger has shifted. It is no longer based on the idea that the sublime is so huge, powerful, unknown and unpredictable that it might sweep you away entirely, and forever, without even noticing that it has done so; the danger now is that the sublime will ingratiate itself to you buy acting hypocritically like the beautiful, then double cross you by turning out to be less that satisfying as such in a new version of the negative pleasure (or bait and switch).

McEvilley, T. (2001) Turned Upside Down and Torn Apart

"McEvilley: Along with formlessness, the theme in recent art involved a sense of the human individual possessing in a hidden way a potential for vast spiritual greatness...

Kelley: I have a big problem with that reading of the sublime. My reading is more Freudian, involved with notions of sublimation. I see the sublime as coming from the natural limitations of our knowledge; when we are confronted with something that's beyond our limits of acceptability, or that threatens to expose some repressed thing, then we have this feeling of the uncanny. So it's not about getting in touch with something greater than ourselves. It's about getting in touch with something we know and can't accept - something outside the boundaries of what we are willing to accept about ourselves."

Mike Kelley In Conversation With Thomas McEvilley (1992)

Morley, S. Ed. (2010) The Sublime, Whitechapel Gallery and the MIT Press, UK & US.